Opus 81

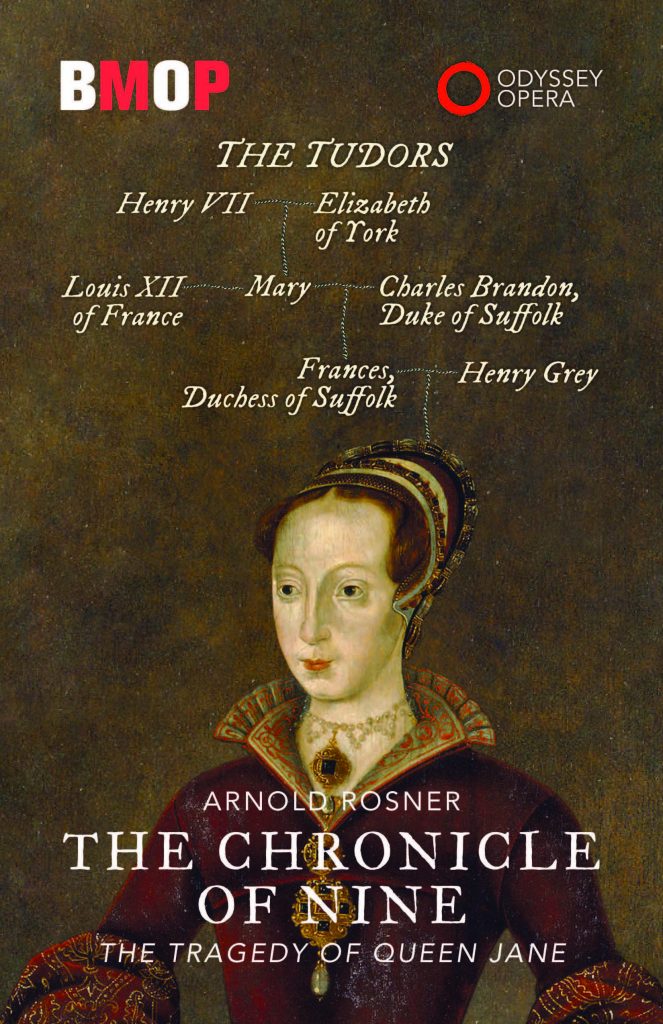

The Chronicle of Nine: The Tragedy of Queen Jane (1984)

for Soprano, Two Altos, Four Tenors, Two Baritones, Bass, SATB Chorus, Orchestra (Opera in Three Acts)

Libretto by Florence Stevenson

Libretto by Florence Stevenson

Duration: 120 min.

Recording: BMOP/sound 1081

Premiere: 2020; Odyssey Opera; G. Rose; New England Conservatory, Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Contact us regarding perusal or performance materials.

The Chronicle of Nine: The Tragedy of Queen Jane is in the copious tradition of operas about thrones and those who jockey around them: in this case concerning the character of Lady Jane Grey (ca. 1537–1554), whose marriage and ascendancy were arranged more or less in spite of her, and who was overthrown and ultimately condemned by the forces of the (rightful) Mary (Tudor). The libretto is by Florence Stevenson and combines a straightforward dramatization of the events with great sensitivity to the people who lived them. Several important scenes in the opera are duets. The composer has tried to intensify the mood of these both melodically and coloristically: the love duet between Jane and her (arranged) husband Guildford Dudley emphasizes harp and vibraphone; the dialogue for Jane and Mary before the execution uses only an accompanying ensemble of six cellos. Of course, there is still room for grand crowd scenes and heavy orchestral preludes; indeed, the four orchestral movements have been extracted to form Symphony No. 7, “The Tragedy of Queen Jane.”

The Chronicle of Nine: The Tragedy of Queen Jane is in the copious tradition of operas about thrones and those who jockey around them: in this case concerning the character of Lady Jane Grey (ca. 1537–1554), whose marriage and ascendancy were arranged more or less in spite of her, and who was overthrown and ultimately condemned by the forces of the (rightful) Mary (Tudor). The libretto is by Florence Stevenson and combines a straightforward dramatization of the events with great sensitivity to the people who lived them. Several important scenes in the opera are duets. The composer has tried to intensify the mood of these both melodically and coloristically: the love duet between Jane and her (arranged) husband Guildford Dudley emphasizes harp and vibraphone; the dialogue for Jane and Mary before the execution uses only an accompanying ensemble of six cellos. Of course, there is still room for grand crowd scenes and heavy orchestral preludes; indeed, the four orchestral movements have been extracted to form Symphony No. 7, “The Tragedy of Queen Jane.”

As for titling the opera, The Chronicle of Nine was the original name of Ms. Stevenson’s stage play, and she meant it to refer to the number of days of Jane’s reign. But in the opera the title refers not only to that but to the number of active singing roles and the number of scenes in which there is vocal action. (The compose tries to ascribe to coincidence the opera’s nine-squared opus number—81!)

For much of the text, the vocal music is less in a set-aria tradition than in the manner of impassioned-recitative or through-melody, as one finds in one way or another in such operatic composers as Monteverdi and Wagner. In the English language, however, perhaps the closest comparison is with Vaughan Williams’s Riders to the Sea. In part for contrast to this, a tenor, acting as a minstrel, sings an introductory vocal ballad between the prelude and first scene of each act; these are of a more “arioso” style and relate to the style of Elizabethan lute songs. (Arnold Rosner)

The work was premiered in February 2020 in Boston, Massachusetts by Odyssey Opera and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project under the direction of Gil Rose and recorded for release on the BMOP/sound label. The cast was: Lady Jane Grey (Megan Pachecano); Earl of Arundel (James Demler); Earl of Pembroke (David Salsbery Fry); John Dudley (Aaron Engebreth); Lady Dudley (Krista River); Guildford Dudley (Eric Carey); Henry Grey (William Hite); Frances Brandon Grey (Rebecca Krouner); Lady (Queen) Mary (Stephanie Kacoyanis); A Minstrel (Gene Stenger)

Several excerpts were previously recorded:

The purely orchestral preludes to each of the three acts plus the wedding ballet comprise the four movement Symphony No. 7, “The Tragedy of Queen Jane.”

The three minstrel ballads that precede each act comprise the song cycle Minstrel to an Unquiet Lady.

Jane’s extensive “Good Friday Aria” (Into Thy Hands) from Act I, Scene 2 is also a performable extract and has been separately recorded.

The Story

The opera takes place in London, England during 1553–54. Each act begins with an orchestral prelude followed by an introductory ballad sung by a minstrel. The first of these ballads welcomes the audience and prepares them for a sad story. The action of Act 1 centers around Jane Grey’s arranged marriage to Guildford Dudley. Jane’s parents inform her of the marriage plans. Jane does not wish to marry and, after arguing with her parents, she rushes out. In the next scene, Jane is alone in her chambers and sings an aria of faith and lament using words from the Passion text in Luke’s gospel: “Father! Into thy hands I commend my spirit.”

A grand wedding ballet (consisting of a series of instrumental dances) marks the marriage of Jane and Guildford. All the guests enter during an opening “Intrada,” with Jane and Guildford at the rear. An elegant “Minuet” is danced by a small group, while most of the wedding party watches from the sides. Jane and Guildford join in near the end. A vigorous “Round Dance” for the entire party follows. The opening “Intrada” returns to conclude the wedding ballet. All the guests bow and salute each other; they exit in a majestic recessional, leaving only Guildford’s parents: John and Lady Dudley.

John and Lady Dudley engage in a discussion. John tells of the ambush that he has planned for Mary Tudor. However, he is paranoid and very worried that people are plotting against him, even though he can find no concrete proof. While John and Lady Dudley worry about the future, they do feel confident that Jane will be proclaimed queen and that Mary will be crushed by their military forces. It begins to hail: rusty-colored hailstones (as if tinged with blood). John wonders what sort of omen it might be.

The orchestral prelude to Act 2 is a dirge for the sickly King Edward, who has died. The minstrel then sings of Edward’s death and the robe, jewels, and crown that will mark Jane as queen. Jane is brought to the bustling council chamber to hear the proclamation of Edward’s death and a discussion of the succession. John tells of how Henry VIII named Mary and Elizabeth as heirs, but their brother Edward decided otherwise because Mary was Catholic and Elizabeth was the daughter of Anne Boleyn. Edward thus passed the succession to Lady Frances Brandon (Jane’s mother) who has passed it to Jane. Jane protests again that she does not wish this position, but her objections are ignored, and all vigorously proclaim her to be queen.

During the grand proclamation, the Earl of Pembroke and the Earl of Arundel slip away from the group to climb to a distant balcony high above the council chamber. Pembroke and Arundel are secretly loyal to Mary, and they discuss their treacherous plan to support Jane’s coronation publicly while simultaneously plotting to aid Mary. Arundel had warned Mary of John Dudley’s ambush plot, so she was able to escape to safety. Pembroke comments that he is sorry that young Jane will suffer for a situation that was not her doing. An impassioned Arundel tells him to spare no sympathy for any Dudley (even one by marriage); he tells of how John Dudley had imprisoned him and shares his delight at soon achieving his bloody revenge against the Dudleys. Pembroke and Arundel discuss their plan to trick John into bringing his forces out from the fortified tower so that Mary can attack him successfully. They depart after pledging their continued loyalty to Mary.

In the military planning room, Jane and her advisors prepare to defeat Mary when she marches on London. Pembroke says that somebody important must lead the troops to victory: Jane’s father (Henry Grey) or father-in-law (John Dudley). Jane seizes upon the suggestion of sending John Dudley (who was planning to defend the tower) out in front. Though slightly reluctant at first, John agrees to lead and ride for his queen. Secretly, Pembroke and Arundel are delighted that their trick has worked, as they know that the defeat they are engineering will greatly weaken Jane’s position.

The battle and defeat are depicted in the orchestral prelude to Act 3: a brilliant clarion battaglia that eventually dies away to nothing. After the prelude, the minstrel begins Act 3 by singing of John Dudley’s defeat, Mary’s ascension to the throne, and Jane’s imprisonment; at the end, he describes the bright sunlit Monday, approaching the day of Jane’s beheading. Jane’s husband, Guildford, is allowed to visit her in prison. Although married, they have not consummated their relationship, and the opening scene, though tentatively at first, is something of a love duet. At the end, Jane sings of her hope that she is now pregnant with a son and muses on Queen Mary’s kindness, while Guildford sings tenderly of the kindness of “this queen” (meaning Jane).

Mary visits Jane’s prison cell. Although initially she had hoped to spare Jane’s life, Jane’s father and uncles, under the leadership of Wyatt, have again attempted to proclaim Jane as ruler; but their rebellion has failed. To protect the crown from further jeopardy, Mary says with regret that she cannot sign Jane’s pardon, and thus the execution will proceed. In order to assuage her own conscience, Mary tries to get Jane to admit that she was personally guilty of the plots against her. Jane refuses to do so, and Mary admits that it is a cruel thing she must now do. Mary will send her priest to say prayers for Jane. Jane answers that Mary has more need for these prayers than she does.

The final scene begins with a version of the “Cries of London”—the street vendors hawk their wares (strawberries, plums, oysters, charms against the plague, etc.). There is an undercurrent of dread as the crowd acknowledges the impending execution of Jane: “A child for the gallows.” Mary and Arundel observe the gathering crowd from a balcony. A regretful Mary still considers signing a pardon for Jane. However, Arundel convinces her it is necessary and even compares Jane’s death to an ancient custom of child sacrifice to ensure a fruitful harvest. While Mary is skeptical, she does not sign the pardon. The vendors and crowd continue to gather, and their cries grow in intensity. The hanging block is moved into position, and Jane is brought forth. Jane sings her farewell: she proclaims her innocence though admits that she was perhaps complicit in her silence. She again quotes from the Gospel of Luke: “Into thy hands, I commend my spirit, O God!” The crowd is full of morbid expectation. Arundel is triumphant, while Mary looks away sadly. Jane is beheaded, and the crowd disperses. (Carson Cooman)